This article is part of a series on Minnesota LGBT history in honor of LGBT History Month. These are excerpts from a forthcoming book for TheColu.mn on the history Minnesota marriage equality debate from 1969-2013.

Steve Endean knew the ins and outs of LGBT activism and lobbying due to his time in Minnesota. He, along with DFL activists Larry Bye and Allen Spear, founded the Minnesota Committee for Gay Rights in the early 1970s (Lesbian was later added to become the Minnesota Committee for Gay and Lesbian Rights). He played a large part in passing Minneapolis’ and St. Paul’s nondiscrimination ordinances.

St. Paul’s would eventually be repealed by the voters in 1978.

Endean had gotten word that religious right activists inspired by Anita Bryant had come to Minnesota to try to repeal Minneapolis’ and St. Paul’s nondiscrimination ordinances, so he called a community-wide meeting in St. Paul.

That meeting spawned St. Paul Citizens for Human Rights. Kerry Woodward became campaign manager, and Endean the assistant manager. Woodward recalled those efforts in an interview with the Minnesota Historical Society’s Gay and Lesbian Oral History project:

Steve should have been the manager, he had done all the advance work on it and he had the strategy and know how. But, over the years he had developed a few enemies in the gay community, in the sense that they didn’t want him to be in charge of the campaign. He asked me if I would be willing to do it. I said I would if there was support from the community and he would support me with his know how because, I didn’t really have the understanding of the strategy in a campaign that Steve had. He had more experience than I did and, I need that experience to manage the campaign. That was agreed to and I got a lot of support. What happened was that I was the manager of the campaign and Steve was the assistant manager but, it worked out to be that we worked more like co-managers. I did a lot of the field organization and the work of keeping the community together and community relations. Steve did the fund-raising and strategy work.

The St. Paul ordinance was repealed by the voters in 1978 after a tough battle, and protections for gay and lesbian citizens disappeared overnight. It left the community disorganized and vulnerable to attack. Woodward recounted those feelings:

After the campaign, the defeat, my sense was that the community pretty much fell apart. People weren’t sure where to go next, what to do next in terms of organizational goals, supporting one another. There was a man who had been beaten to death on the head with a lead pipe by some anti-gay man. People had their car tires slashed outside gay bars in St. Paul. Stuff that would happen from time to time but, not as often and not with the viciousness that was happening after the St. Paul campaign. It was as if that vote had given license to anti-gay violence. The organization of the St. Paul ordinance (St. Paul Citizens for Human Rights) was closed so, that was no longer available as a unifying force. Obviously, if the St. Paul ordinance had been repealed there was no chance of getting anything passed for years in the state Legislature so, MCGLR’s goals were, in a sense, hopeless at least for several years. [The question for MCGLR] What do you do in the interim until once again there is a chance for passing that kind of legislation. I think there was generally a feeling of possibly depression, an immobility in the community. It was definitely a time that was right for new leadership to come in forward and bring in new goals and actions.

Endean left Minnesota to work on the Gay Rights National Lobby in Washington, DC, the first major lobbying organization for the LGBT community. Woodward moved to California, as did Larry Bye, another Minnesotan involved in the founding of HRC.

They’d all left after the bruising defeat in St. Paul, according to Out For Good: The Struggle to Build a Gay Rights Movement in America by Dudley Clendinen and Adam Nagourney (Clendinen and Nagourney note that much of the early organizing in America involved Minnesota and Minnesotans).

HRC was officially incorporated in Washington, DC, on April 14, 1982 by Steve Endean as the Human Rights Campaign Fund, a non-profit political committee.

The first board of directors of HRC included Minnesota natives Kerry Woodward, Larry Bye, and James Hormel, heir to spam-producing Hormel Foods in Albert Lea.

Other board members included Virginia Apuzzo, Jerry Berg, John Campbell, Dallas Coors, Gilberto Gerals, Ethan Geto, Rev. Elder Jerri Ann Harvey, Paul Kuntzler, Bettie Naylor, Lois Galgay Reckitt, and Jerry Weeler.

Woodward was co-chair, Endean was executive director. The first lists of donors came from the battles against Anita Bryant in Dade County, St. Paul, Wichita, and Eugene.

It was Bye’s idea to call the new group the Human Rights Campaign Fund, he was also charged with drafting the plans for the fledgling organization.

James Hormel, in his book, Fit to Serve, recounted the naming of the group:

The new group, the Human Rights Campaign Fund, was launched in 1980. In the temper of the time, the name intentionally omitted the words gay and lesbian. From a philosophic point of view, we wanted to keep the focus on what we stood for: a simple extension of civil rights and basic fairness. Practically, we knew that the inclusion of those words would decrease our ability to raise and dispense funds at a time when we needed to engage as many supporters as possible. We wanted to steer clear of titles that might incite the Swiftboaters and Birthers of those days, or cause people to withdraw rather than participate.

The HRC dinner, which has annually served as a major fundraising and visibility tool for the organization, was created in 1982, and the founders knew they had to get a big name to speak. They reached out to another Minnesotan.

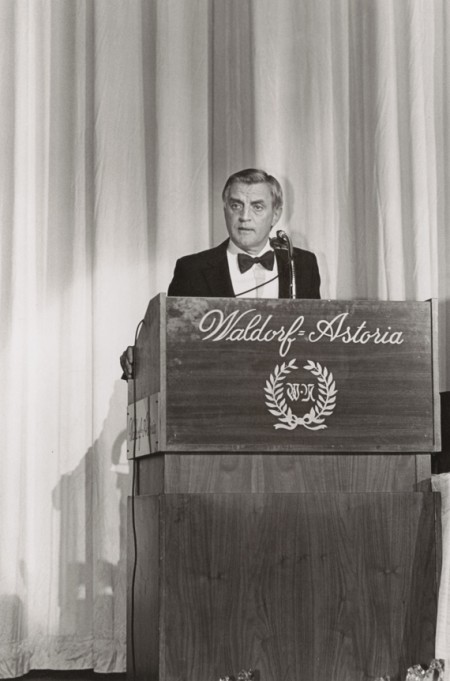

The new group courted former Vice President Walter Mondale for the first HRC dinner. Minnesotans Endean, Woodward, and Hormel, as well as Dan Bradley met with Mondale. Hormel wrote, “With three of the four of us from Minnesota, how could Mondale refuse the invitation?”

After some hemming and hawing, Mondale spoke at the first HRC dinner.

The organization continued to pick up donors and respect in the mainstream of American politics.

But the controversial politics surrounding HRC today — a mainstream, assimilationist approach and the perceived apathy toward issues affecting rights for transgender community — were present early in its Minnesota roots.

In the late Sen. Allen Spear’s autobiography, Crossing the Barriers, he recounted how local activists viewed Endean’s mainstream approach. Tim Campbell, who published the long-running GLC Voice, and Jack Baker, who had sparked the nation’s first marriage equality lawsuit, were two people who were particularly at odds with Endean’s approach.

[Campbell’s] priorities were somewhat different. While Jack focused on gay marriage, Tim was particularly concerned with sexual liberation, cross-dressing, and the rights of transgender people. But he shared with Jack a commitment to an “in your face” approach to politics and a disdain for the kind of “within the system” tactic that Steve Endean and I were advocating. After the successful effort in St. Paul [to add a gay rights ordinance], Tim wrote Steve , congratulating him on the outcome, but criticizing a flyer Steve had posted in the gay bars urging people who came to lobby not to “be so flamboyant as to alienate possible supporters.” “We know”, the flyer had continued, “that gay people don’t fit those tired stereotypes that some straights label us with.

Those early criticisms of HRC’s founder were echoed in the late-2000s when the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) was gaining steam in Congress and HRC was considering leaving gender identity by the wayside in order to get the bill passed (it did not pass).

As writer Monica Roberts noted in 2007, “One of the people most responsible for excluding transpeople from an attempt to pass a gay rights law in Minnesota in 1975 was a gentleman by the name of Steve Endean, who in 1980 would leave Minnesota to help found the Human Rights Campaign Fund, the proto organization that later became HRC. Some Minnesotans assert that it’s not a coincidence that the same year HRCF was born in DC, Minnesota’s gay rights proposals became T-inclusive and eventually lead to the first T-inclusive law in 1993.”

HRC’s focus on marriage equality also became a target of protesters at a 2009 HRC dinner in Minneapolis.

HRC has taken strides in recent years to put transgender issues to the forefront.