Stewart Van Cleve is a library assistant working with the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection at the University of Minnesota, and compiler of the 100 Queerest Places in Minnesota History. This is the first installment of Stewart’s new, regular column on queer Minnesota History.

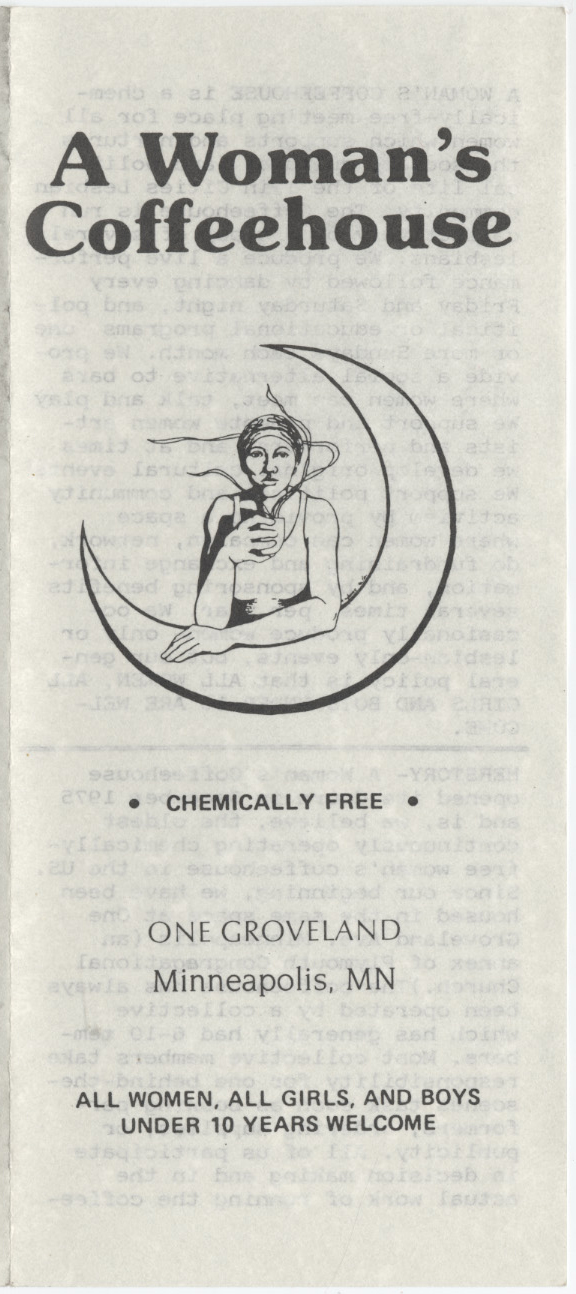

In 1975, a group of lesbian-identified women organized an alcohol-free night of performances and dancing at the Lesbian Resource Center in south Minneapolis. [1] The evening was a surprising success, and its organizers formed a collective to continue offering a “sober space, women’s space, celebration space, forum space, caring space, and sharing space”[2] to the lesbian and bisexual community. After a few more meetings at the Resource Center, the Collective relocated to the basement of the Plymouth Congregational Church on the southern edge of downtown Minneapolis.

The Collective’s appearance marked a point of departure in the social scene of Minnesota’s queer women—before ’75, women either met through quiet social networks and house parties, by participating in activist organizations, or they socialized in the respective lesbian-designated bar that operated at the time. A Woman’s Coffeehouse was one of the first community-run social spaces that attempted to blend the sociability and safety of house parties with the visibility of lesbian bars.

At the time of the Coffeehouse’s founding, many women feared participating in political movements or entering “known” lesbian spaces. The FBI kept tabs on several Gay and Lesbian activist organizations during the Nixon Administration (1969-1974); in some cases, agents infiltrated radical groups with instructions to spread discord, take names, and orchestrate raids.[3] Paranoia among queer women was abundant, and it conflated fears of arrest, fears of being “outed,” and fears of losing gainful employment. Toni McNaron and Karen Clark both participated in “the Coffeehouse” during the mid-1970s, and considered their attendance as a risk to their livelihoods.[4] This ultimately proved to not be the case; McNaron became a respected University of Minnesota professor and Clark became one of the first openly-lesbian politicians in the United States.

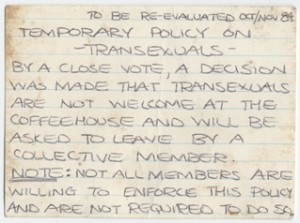

Several lesbian bars and alternative social organizations (such as Out to Brunch) organized and opened in the mid-1980s and actively competed with the Collective’s once-unique status as a social venue for women. The Coffehouse’s competitors offered an easygoing alternative to the contention of regular meetings. Thus, the majority of women who just came to dance went elsewhere. Membership dwindled, and the organization closed in September of 1989.[6] A decade later, many of the Coffeehouse’s pioneering members held one last event in the basement of the Plymouth Church, where women had established lifelong friendships and relationships for more than fifteen years.

[1] Enke, Anne. Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism. North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2007. Page 224.

[2] Excerpt from a speech by an unidentified woman, recorded at a Woman’s Coffeehouse Collective meeting on 2/9/85.

[3] Glick, Brian. War at Home: Covert Action Against U.S. Activists and What We Can Do About It.” Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1989. Page 27.

[4] Enke, page 225.

[5] Anderson, Shelley. “Coffeehouse Makes Changes.” Equal Time, 12/18/1985. Page 9.

[6] Dryer, Peg and Porte, Trina. “The Coffeehouse: A Final Accounting.” Equal Time News, 8/3-8/17/90. Page 4.

Thanks for this Stewart! So many of the stories of the early days of Minnesota LGBT history are forgotten or simply lost forever. Look forward to more of these!

I spent many an evening as a child at the coffeehouse! My mother and her partner and I lived in a communal house with three of the board members and if there wasn’t SOME sort of coffeehouse drama going down, it wasn’t worth getting out of bed.

Comments are closed.