Young activists, political radicals, and University of Minnesota graduates took over a rundown single-family home on Ridgewood Avenue (now demolished) in 1971 to create a first in the state. Gay House was literally a house of, by, and for gay people—selected for its close proximity to the former nucleus of Minneapolis’ “gay ghetto,” the structure served as an office building, meeting space, and crash pad for young people in need of help as they struggled to come to terms with their identity. Led by Jim Frost, a group of volunteers set up a telephone hotline to counsel troubled youth in the Twin Cities.

The Gay House hotline and its positively gay volunteers became immeasurably successful; the center received 50,000 phone calls and provided counseling services to well over 5,000 by 1975.[i] Thematic similarities in the callers’ problems surfaced; clients frequently desired basic information about sexuality, and they sought perspectives from others who shared their pain. With the help of Michael McConnell, a librarian fired by the University of Minnesota for gay activism—Gay House offered the first-community-run queer library in the Upper Midwest. Organizers reached out to new gay and lesbian publications in larger cities, including The Los Angeles Advocate, and contacted librarians for bibliographies. Barbara Gittings—founder of the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis and editor of its magazine, The Ladder—sent Gay house a bibliography and a message to “keep on gay-ning.”[ii]

To Steve Endean, the future founder of the Human Rights Campaign in Washington, D.C., Gay House was a brave first step towards self-acceptance:

“…I was straightlaced and was somewhat taken aback by the ‘early Salvation Army’ look of the drop-in center. Inside, I met several outrageous counterculture queens who seemed to personify every stereotype I’d heard about. But since it was basically clear that my sexuality wasn’t just a phase but a reality, I was incredibly anxious to meet people that might assist in helping me develop a positive self-image as a gay man.”[iii]

The differing personalities of “counterculture queens,” straight-laced activists, and troubled youth often produced conflict. Gay house’s “rap sessions” inspired everything from genuine synergy to complete dissension. Meetings occasionally devolved into a series of “loud, angry, and seemingly pointed requests…for participation in some activities.”[iv] One anonymous participant complained “the house was basically run by kids above 18 for kids below 18.”[v] Four years and a move to south Minneapolis later, these and other interpersonal issues forced the center to close in 1979.

Ultimately, the legacy of our first community center offsets its negative end. Some of our most important institutions, such as OutFront Minnesota, the Twin Cities Pride Committee, and the All God’s Children MCC have roots in Gay Houses’ seat-of-the-pants activism. Without it, the Twin Cities would have likely been much less livable.

[i] “Gay House Starts Fifth Years of Service.” Gay House Newsletter, 7/14/75.

[ii] Barbara Gittings Letter, OutFront Minnesota Collection, Box 1. Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, University of Minnesota Libraries.

[iii] Steve Endean and Vicki Lynn Eaklor, Bringin Lesbian and Gay Rights Into the Mainstream: Twenty Years of Progress (New York: Harrington Park Press, 2006), 11

[iv] Sic.

[v] “Open House-Meeting at Gayhouse [sic]” Hundred Flowers, 10/1/71. Page 11.

It is nice to get a slice of historical gay Minneapolis from time to time. We lost so many of our ancestors to HIV that institutions may have to step into the niche of storytelling to keep our active history alive. Thanks to TheColu.mm & Stewart Van Cleve for this piece.

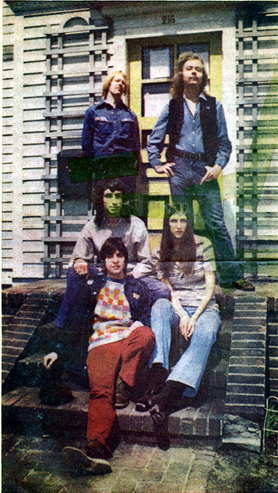

[…] Gay House in Minneapolis […]

Comments are closed.